A REUTERS SPECIAL REPORT

When Eritrea sent troops into the Tigray region, the secretive nation seized a double opportunity: It detained thousands of Eritrean refugees as it battled Ethiopia’s former rulers. Spearheading the bloody campaign: a colonel nicknamed ‘Son of Bread’

ADDIS ABABA

Over two decades, Eritreans poured across the border into Ethiopia, fleeing forced military service, torture, and prison in one of Africa’s most repressive states. By last November, around 20,000 of them were living at two refugee camps here in Ethiopia’s Tigray province, finding haven in their more prosperous neighbour.That month, rebellion broke out in Tigray, pitting the region’s rulers against Ethiopia’s central government. The Eritrean military sent in tanks and troops to aid its ally, Ethiopian leader Abiy Ahmed – and to settle old scores.Within days, truckloads of soldiers from the 35th Division of the Eritrean Army arrived at the two refugee camps, Hitsats and Shimelba. The soldiers had lists of names.In Hitsats, where undulating hills wrapped around the camp’s white tents and corrugated iron shacks, soldiers called refugee leaders to a meeting. The 20 or more who complied were detained, said more than a dozen witnesses, one demonstrating how the men’s elbows were pinioned behind their backs. They were held for two days at a church building in the camp, then loaded onto trucks by Eritrean soldiers and driven away, the witnesses said. Reuters has confirmed the names of 17 of the men. Their families haven’t heard from them since.

Similar scenes played out in Shimelba, about 15 kilometers (9 miles) from the Eritrean border. “They were looking for members of the opposition. They had a list,” said a Shimelba refugee leader.

The Eritrean soldiers detained around 40 people there, some of them women, said the refugee leader. Like most others interviewed for this article, he spoke on the condition that his name be withheld to protect his family in Eritrea and for his own safety in Ethiopia.

The arrival of the Eritrean troops marked the beginning of a months-long ordeal for thousands of Eritrean refugees – first hunted by the Eritrean military, then attacked by Tigrayan fighters who accused the refugees of conspiring with the enemy.

Reuters spoke to more than 60 refugees. These interviews revealed the role of the Eritrean Army division and commander who led the campaign to force the refugees back to Eritrea. Eritrean soldiers then destroyed the camps.

The refugees told of a systematic military operation: At a border town, Eritrean soldiers set up a COVID-19 quarantine centre, staffed by Eritrean doctors; soldiers then bussed thousands of refugees into Eritrea. Some went at gunpoint; others said they went voluntarily, swapping the perils of Tigray for the uncertainties of their homeland. The refugees also told for the first time how, once in Eritrea, some of their number were jailed or forced into military service.

“(The Eritrean soldiers) were looking for members of the opposition. They had a list.”

A former top-ranking Eritrean military officer, now in exile, told Reuters he has seen Eritrean government documents that show more than 9,000 refugees returned to Eritrea. Reuters was unable to obtain these documents. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) told Reuters in a statement its teams have interviewed several hundred refugees who say they escaped after a forced return to Eritrea. The agency estimates 7,600 refugees are still missing. Some have likely moved to the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, UNHCR said.

The refugees interviewed by Reuters spoke of killings, gang rapes and looting both by Eritrean soldiers and Tigrayan fighters. Some incidents in late 2020 and early 2021 are documented in a recent report by Human Rights Watch. Refugees told Reuters attacks by Tigrayans have continued, including lynchings in June in the northern town of Shire.

Eritrea has denied that refugees were forcibly returned. It has also rejected accusations that its forces killed Tigrayan civilians and forced some into sexual slavery, as first revealed by Reuters. In August, the United States imposed sanctions on the chief of staff of the Eritrean military, Filipos Woldeyohannes, saying forces he commands committed atrocities, including massacres and sexual assaults. Eritrea dismissed the charges at the time as “utterly baseless.”

Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy has said he has assurances from Eritrea that it will hold to account any soldiers found guilty of abuses. His spokeswoman, Billene Seyoum, did not respond to Reuters questions about whether any Eritrean soldiers had been charged. Eritrea’s government and military did not respond to detailed questions for this article.

Debretsion Gebremichael, the head of the party that controls most of Tigray, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), said his organization had no knowledge of attacks by Tigrayan fighters on Eritrean refugees. Tigrayan soldiers were ordered not to enter the refugee camps, he told Reuters. TPLF spokesman Getachew Reda said it was possible there were “vigilante groups acting in the heat of the moment.” Getachew did not respond to questions about whether the TPLF was investigating alleged crimes.

The refugees’ plight shows how Tigray has become the crucible of a power struggle between Ethiopia’s government and the TPLF, a guerilla movement-turned-political party that once dominated the country. The civil war has drawn in the authoritarian government of neighbouring Eritrea. Led by President Isaias Afwerki, Eritrea views the TPLF as its arch enemy and Tigray as a haven for refugee dissidents. For the first five months of the conflict, Eritrea denied its soldiers were inside Tigray. The Eritrean army continues to operate in northern Ethiopia, according to witnesses.

Ethiopia – home to 109 million people – is Africa’s second-most-populous nation and has been a key Western ally in an unstable region. For years it was Africa’s fastest-growing economy, and when Abiy took power as prime minister in 2018, he was hailed as a democratic reformer.

But the country is now in crisis. The war in Tigray has cost thousands of lives, triggered a famine and displaced more than 2 million people. Tiny Eritrea, a land of just 3.5 million people, plays an outsized role in the chaos.

Old enemies

Enmity between Eritrea and the TPLF runs deep. The TPLF dominated Ethiopia’s government for nearly three decades and fought a border war with Eritrea in 1998-2000. Abiy made peace with Eritrea months after becoming prime minister. The deal earned him the Nobel Peace Prize – and, in Eritrean President Isaias, a powerful ally against the TPLF.

Hitsats and Shimelba were two of four camps for Eritrean refugees in Tigray. Poor but peaceful, they were run by Ethiopia’s Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) and UNHCR. Some residents built tiny, windowless huts from stones or wattle and daub. Others set up small restaurants or kept animals to earn a few pennies.

UNHCR says Eritrea generated the world’s third-largest number of refugees per capita in 2020, behind Syria and South Sudan. About 15% of its people – more than 520,000 – have fled. Around 150,000 of these refugees have made their way to Ethiopia; 96,000 lived in Tigray. Eritrea insists those who have left are economic migrants.

Many of the Eritrean refugees in Hitsats and Shimelba recounted brutal treatment in their homeland. With no free media and no elections, Eritrea has been described by some Western media and think tanks as “the North Korea of Africa.” Men and unmarried women over the age of 18 are conscripted into indefinite military or government service. Some told Reuters they had been forced into it years earlier. One refugee, a grey-haired military deserter who retains a soldier’s posture, told Reuters his family left Eritrea after soldiers came to his home and smashed his 14-year-old son in the face, demanding to know the father’s whereabouts. The boy still has a scar. Medical scans, seen by Reuters, show a skull fracture.

“The government will forgive you”

Soldiers from the 35th Division of the Eritrean Army reached Hitsats on Nov. 19, according to refugees at the camp and people living in the vicinity. The camps lay in an area where the Ethiopian Army had no presence at the time, local residents said.

The soldiers were led by an officer who introduced himself as Wedi Kecha, said two refugees, who previously served under him in the Eritrean Army and knew him by sight. Two campaigners for the rights of Eritrean refugees – British-based Elsa Chyrum and an activist in the United States – told Reuters that refugees they spoke to also identified Wedi Kecha as the commander. The former top-ranking Eritrean military officer confirmed to Reuters that Wedi Kecha leads the 35th Division.

Wedi Kecha didn’t respond to questions sent by Reuters via the Eritrean military. The Eritrean Army didn’t comment about Wedi Kecha’s role.

The soldiers gathered the refugees outside a church hall in the camp on Nov. 21. “Wedi Kecha introduced himself as the commander of the 35th Division,” said one of the refugees present, who served under Wedi Kecha in the Eritrean Army in the 1990s and spent two years stationed at the same base as him within the last decade. Wedi Kecha, this refugee said, “means ‘Son of Bread.’ It’s a nickname he has had since childhood.”

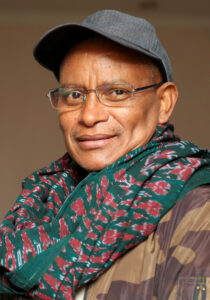

Wedi Kecha’s real name, according to this refugee and the former top-ranking Eritrean military officer, is Colonel Berhane Tesfamariam. Wedi Kecha fought in Eritrea’s war of independence from Ethiopia, which ended in 1991, the former top officer said. He is believed to be in his 60s. According to the refugee, Wedi Kecha was an excellent footballer in his younger days and used to play as a midfielder for a team that competed at a national level.

Wedi Kecha told the crowd that his soldiers had come to protect the refugees. He invited the refugees to return to Eritrea, telling them, “the government will forgive you.”

Soldiers from the 35th Division also came to Shimelba, according to refugees there. At a meeting on a football pitch at the camp on Nov. 18, leaders were addressed by an officer – described by one refugee as elderly, tall and strong, and identified by another as Wedi Kecha. The officer told the refugees that the soldiers were there to protect them. It was safe to return to Eritrea, he said, but if the refugees chose to stay, no one would help them.

- Read More on reuters.com